By Tom Switzer, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 2018

By Tom Switzer, Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 2018

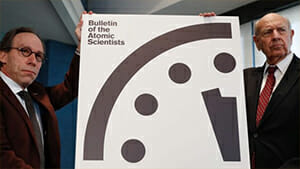

For seven decades, the Chicago-based Bulletin of Atomic Scientists group has kept a symbolic device called the Doomsday Clock. Its purpose is to warn humankind about the prospects of apocalypse.

At the onset of the Cold War, in 1947, the clock was set at seven minutes to midnight. Midnight, of course, means the moment we’re all annihilated. Ever since, the minute hand has yo-yoed between two and 17 minutes before catastrophe. It wavers in accordance with the judgment of prominent scientists and strategists about the state of global order. For instance, the clock’s hand was pushed forward to two minutes to midnight in 1953 when the US and the Soviet Union conducted atomic tests; it was pushed back to 17 minutes to midnight in 1989 when the Berlin Wall fell.

Last week, it was moved significantly closer to Armageddon by 30 seconds to two minutes to midnight. The eminent group, which includes 15 Nobel laureates, is raising alarm bells because Donald Trump and other world leaders have failed “to deal with the looming threats of nuclear war and climate change”.

What is one to make of all this? The first point to keep in mind is we are still here. Throughout much of the Cold War, many of the same types of experts warned the world was on the cusp of a nuclear disaster, one that would occur unless there was nuclear disarmament. And yet, as far as the US and Soviet Union were concerned, the Cold War turned out to be “the long peace” as prominent diplomatic historian John Lewis Gaddis calls it. For four decades, not a shot was fired in anger between the superpowers. This was because the threat of mutually assured destruction generated fear and caution in Moscow and Washington.

In 1983, Australian anti-nuclear activist Helen Caldicott warned: “If Ronald Reagan is re-elected, accidental nuclear war becomes a mathematical certainty.” This was the same Reagan – re-elected in one of the biggest landslides in American history – who went on to negotiate arms-control deals with the Soviets that led to the end of the Cold War.

The board of directors of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists have hardly been alone in peddling doom and gloom. In the 1970s, a committee of distinguished intellectuals called the Club of Rome confidently predicted widespread famine as well as economic stagnation and scarcity of resources. We were told that unless prompt and drastic action was taken to limit population and industrial growth, the world would face disaster by the end of the 20th century.

And yet population growth estimates have declined. Biotechnology advances have found ways to reduce global poverty dramatically. Oil, among other natural resources, has hardly run out. And global growth, according to the IMF, is scheduled to record annual robust rates of nearly 4 per cent on the back of US tax cuts in 2018.

Which brings us to the Trump era. Like the nuclear Jeremiahs and climate catastrophists, the US president is incapable of understatement. He’s also strikingly ignorant and erratic. Yet his record suggests Trump has been nowhere near as dangerous as his rhetoric suggests.

Take North Korea. For all their bellicose talk, Trump and Kim Jong-un are unlikely to come into conflict. This is because nuclear deterrence works. To carry out a nuclear attack on a nuclear power is to become a nuclear target. As leading realist scholar Barry Posen has argued if Pyongyang attacks the US or its allies with nuclear weapons, it will be attacked with many, many more nuclear weapons. Why would Kim, whose ultimate goal is survival, play with Trump’s “fire and fury” threat? And why would Trump strike at North Korea when its leader, with nothing left to lose, could wipe out Seoul or perhaps Tokyo?

Take climate. The environmental doomsayers slam Trump for pulling the US out of the non-binding and non-enforceable Paris climate accords of 2015. Never mind that the shale gas “fracking” revolution has meant lower US emissions. And never mind the net emissions of the China-led developing world are steadily escalating.

Or take globalisation. Trump’s anti-trade populism, like that of the Australian Greens and the economic nationalist wing of the ALP, threatens prosperity. But the candidate Trump who threatened a trade war with China is not the president Trump on display at the World Economic Forum a few days ago. He toned down “America First”, even flagging US participation in a revised Trans-Pacific Partnership. According to The New York Times, “a rough consensus emerged at Davos that the Trump administration had shown itself to be more pragmatic than advertised”.

None of this suggests other predictions of disaster must be false. If a terrorist ever got hold of nukes, the consequences would indeed be grave. My point is that apocalyptic politics reflect so much thinking about the nuclear and climate challenges. Moreover, prediction is far from an exact science even when it is being made by the experts. “Prediction”, Danish nuclear physicist Niels Bohr once observed, “is very difficult, especially about the future.”

Tom Switzer is executive director of the Centre for Independent Studies and presenter at the ABC’s Radio National.

Originally published: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/doomsday-clock-ticking-but-prediction-remains-difficult-20180128-h0pph8.html